This article was originally posted on 3D Printing Media Network

Once upon a time, 3D printing was the next big thing. The 3D printing revolution was eager to deliver a world of make-upon-demand items, we imagined a society free of factories. Instead, each household would have an advanced 3D printer that could conjure up whatever your heart desired.

In many ways, our ideas of 3D printers were heavily influenced by science fiction. Like replicators from Star Trek, we thought that 3D printers could simply print out objects from whatever schematics were available. So long as you had the blueprints and the materials, the thinking went, then you could produce what you needed.

But the reality of 3D printers today is far different. Though these devices remain a niche hobby, fawned over by enthusiasts, most households haven’t snapped up 3D printers like they did desktop computers. Instead, 3D printers have found very specific, specialized applications These may not have been what early visionaries imagined, but 3D printing is here to stay.

Why did the 3D printing revolution fizzle out?

To begin, it’s helpful to understand why 3D printing hasn’t boomed.

To put it simply, most households didn’t need 3D printers. Even hobbyists (who want to tinker with 3D printers and use them on a regular basis) turned to shared makerspaces, where they could rent out 3D printing services on a monthly or as-needed basis. Moreover, as one journalist noted, “home 3D printers are too expensive for amateur tinkering but not sophisticated enough for professional use.”

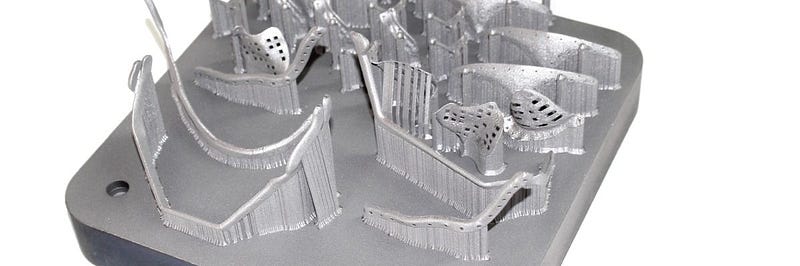

Second, the 3D printing revolution failed to replace manufacturing, a result of economics and design factors. In an article published in the Harvard Business Review, researchers noted that the main challenges facing mass 3D printing include scale and cost of labor. Even when parts can be 3D printed with reasonable efficiency and speed, there are considerable costs in the pre- and post-printing areas–namely duties like computer-assisted design or prototyping. In other words, to shift manufacturing towards mass 3D printing would require expensive upfront investment, especially in terms of creating designs for the desired parts. For now, this is simply too costly to be feasible.

To compare 3D printers to personal computers, note that computers became popular precisely because they could carry out vital, routine functions cheaply and efficiently. For instance, a 1989 article from The New York Times notes that as networks of electronic mail (how quaint!) systems were linked together, they quickly became faster and easier to use than snail mail or fax machines. Still, email was but one of the features that spurred the personal computer boom, as the bottom line was that computers became the best tool for a number of tasks. Such devices also became less intimidating and more accessible as well.

Unfortunately, 3D printing has yet to do the same. But not all hope is lost.

Where 3D printing shines

Instead, befitting its origins as a niche product, 3D printing excels at specialist innovations. Because it remains at the cutting-edge of technology today, its applications are equally innovative, forward-thinking, and unique.

Essentially, 3D printers are best used for targeted, specific functions. Take its numerous medical applications, for instance. In July 2017, Swiss researcherswere able to 3D print a silicone heart which functions much like the real thing. Thanks to the inherently complex nature of 3D printers, the scientists were able to print the device in one go, without having to worry about seams or attachments. Though this device was just a proof-of-concept prototype, it’s still far simpler to implant than current glass-and-steel models, which are considerably more difficult to attach, replace, and repair.

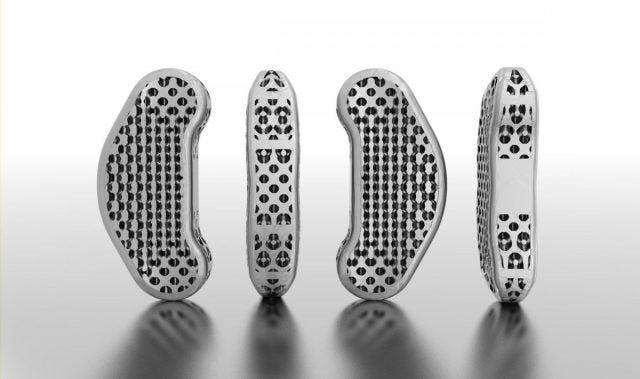

Another area where the 3D printing revolution brought about great change is in prosthetics, where it can potentially reduce sky-high expenses and make the process more customizable and intuitive. Though it’s an outlier, a high-end microprocessor for an artificial limb can cost as much as $150,000; a typical prosthetic without such a chip can still run over $10,000. Even mid-range pneumatic and electronic prosthetics, which can fully substitute for lost limbs, can cost anywhere from $40,000 to $60,000.

That’s where 3D printing can step in. It cuts down on the costs, wait time, and numerous fittings involved in the prosthetics process, greatly improving an unpleasant procedure for an uncomfortable replacement. By using laser scans of existing limbs, engineers can easily and quickly figure out the geometry and dimensions of the replacement and build models accordingly. It’s also much easier to tweak blueprints on a 3D printing program (and simply create a new one) than on a handcrafted component. In fact, one Stanford Bio-X fellow 3D printed a $20 replacement knee.

Moreover, for regions struggling to recover from the aftermath of serious conflict, 3D printed prosthetics can potentially be a godsend. In places like Darfur, even the most basic services can be difficult to come by. Some eight in ten people in need of prosthetics do not possess them (and worse yet, have no way to get them). According to the WHO, there is a shortage of some 40,000 trained prosthetists, especially in poorer nations–which means that patients must travel long distances for a process that can take up to five days.

The 3D printing revolution, however, started to help address many of these challenges. Not only is it relatively cheap (averaging around $50 per prosthetic), but scaling prosthetics for growing children is quite easy; all a designer has to do is open a file, adjust the design, and print out the new one. Even if there are challenges (for instance, plastic prosthetics can melt in hotter climates), for amputees in emerging economies, the way forward is clear.

As recent developments show, the future of 3D printers lies not in mass production, but in specialized applications, such as crafting replacement organs or artificial limbs. As promising as they are, however, much work remains to be done in the areas of process and materials. To really be successful in the demanding environments of developing nations, 3D printers have to become more robust, more user-friendly, and more efficient. In addition, if these devices can be adapted to use sustainable materials (such as upcycled waste plastic), then the dream of a 3D printer in every village or county can finally become reality.

This is where the next growth opportunity in the 3D printing revolution lies: faster, tougher printers that use less material–and are less prone to error. The company which can pull this off will seize control of an underutilized, exciting market–and revive an industry struggling to breakthrough to the mainstream.